According to MIT, some scholars blamed bad note-taking skills for their plagiarism accusations. That may well be true, academic notes have specific requirements that few are aware of. Let’s dive in and see why academic notes are so different.

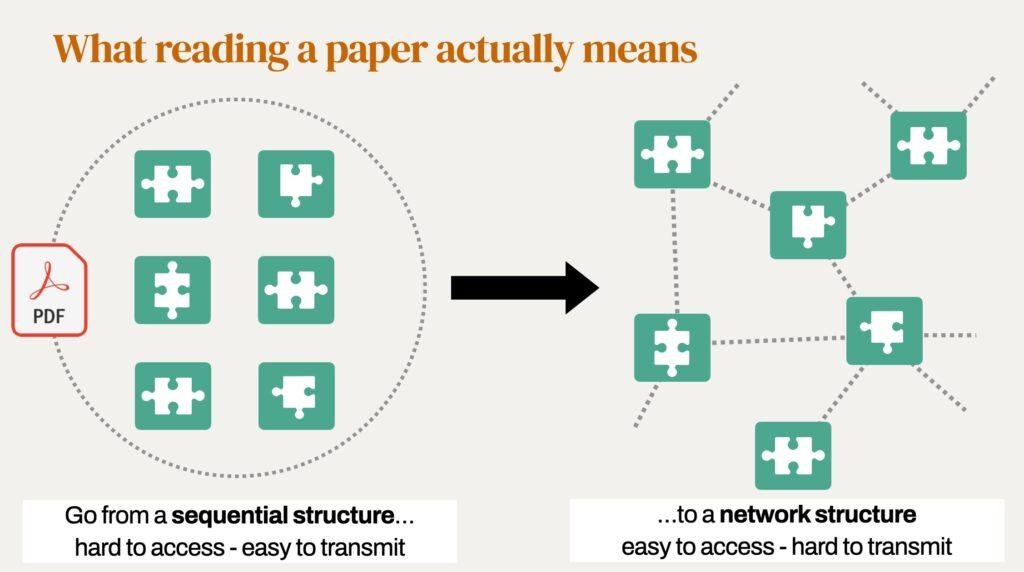

When you read a paper every statement has a source/reference. If it’s original thought it is derived from some data or a solid logical argument. A paper that doesn’t do that, gets sorted out at the peer review stage.

Papers are the result of notes that the authors collected over months and years.

Logically we need to apply the same standards to our notes as we do to our papers. We need to “peer review them” constantly.

For that reason, popular note-taking systems often don’t work as well for academia as they do for non-academia. Just like I can’t write my papers in the same style, attitude, and ease as this blog post.

And lastly what science considers plagiarism is much more confining than you would think. For example, the MIT guide to paraphrasing says that even stating the source is sometimes not enough to prevent plagiarism accusations. You need to use your own words even when expressing somebody else’s ideas and crediting it to them.

So it’s delicate.

In my budding academic career, I experimented for 500+ hours with notes and different tools. These are the 10 commandments my notes taught me (in no particular order).

I. Thou shalt have source notes

These are notes primarily designed to attribute sources. Usually literature, e.g. “Smith 2020”. Don’t aim at summarizing what the authors wrote in this paper too much, try to expand it into concepts and see the source note as a “bridge” between many notes.

It is indeed the gateway to a network:

II. Thou shalt attribute a source to everything

I collect short factual statements in my notes on all the relevant subjects. Each of them has a link attached. If I use any of these statements in my writing I know immediately who to attribute it to.

You can even link to “Smith 2020, Ref 85” if “Smith 2020” is not the primary source of this information.

III. Thou shalt never copy & paste

Copy & Paste even with attribution is plagiarism. Just avoid doing it. Besides you learn much better if you put things into your own words. If you are lazy, at least use ChatGPT to paraphrase and shorten passages to your liking. My note-taking app Obsidian can integrate with ChatGPT, so I don’t have to use the browser.

IV. Thou shalt be brief

Academic writing is often verbose to create a context, explain lesser-known concepts, or drive a point home. Your notes are different! Don’t think of them as finished writing, but rather as reminders to yourself. Even use emojis, mix languages, and do whatever helps you to grasp it quickly.

Your notes will grow much faster than you believe if you keep taking them. If you want to be able to catch up on old concepts, do yourself this favor and be as brief as you possibly can.

V. Thou shalt link as much as possible

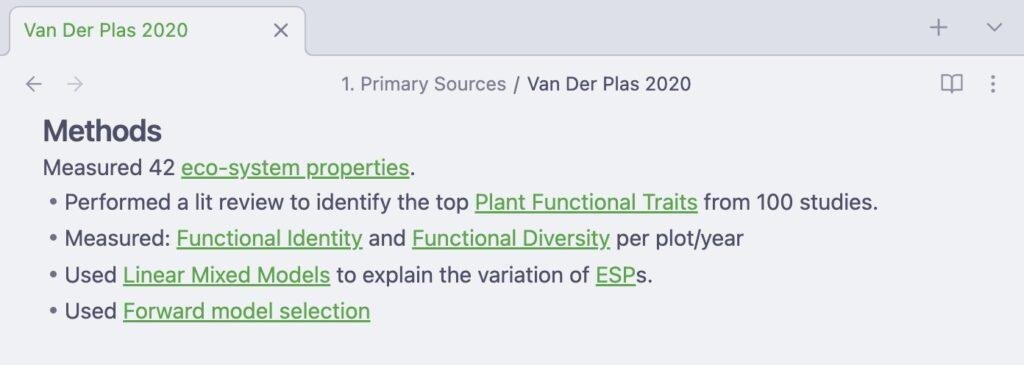

Whenever you find yourself explaining a concept, create a separate note instead. Linking is a way to avoid being verbose. This note sums up ~10 paragraphs of a methods section into less than 50 words for example:

The note is brief but I must remember for example what “Linear Mixed Models”(LMMs) are for it to make sense. In a year I might need to google what LMMs are to understand them. The link however ensures that I can just click it, instead of googling to get all the information needed!

VI. Thou shalt differentiate between fact & fiction

Speculation can cost you an academic career, unless you distinguish it as such and put it into the “discussion” section of your paper. That is why I put a lot of effort into separating my questions, ideas, and thoughts from “factual” statements I read somewhere.

Use special folders or tags for the notes that contain your thoughts.

VII. Thou shalt prepare for writing

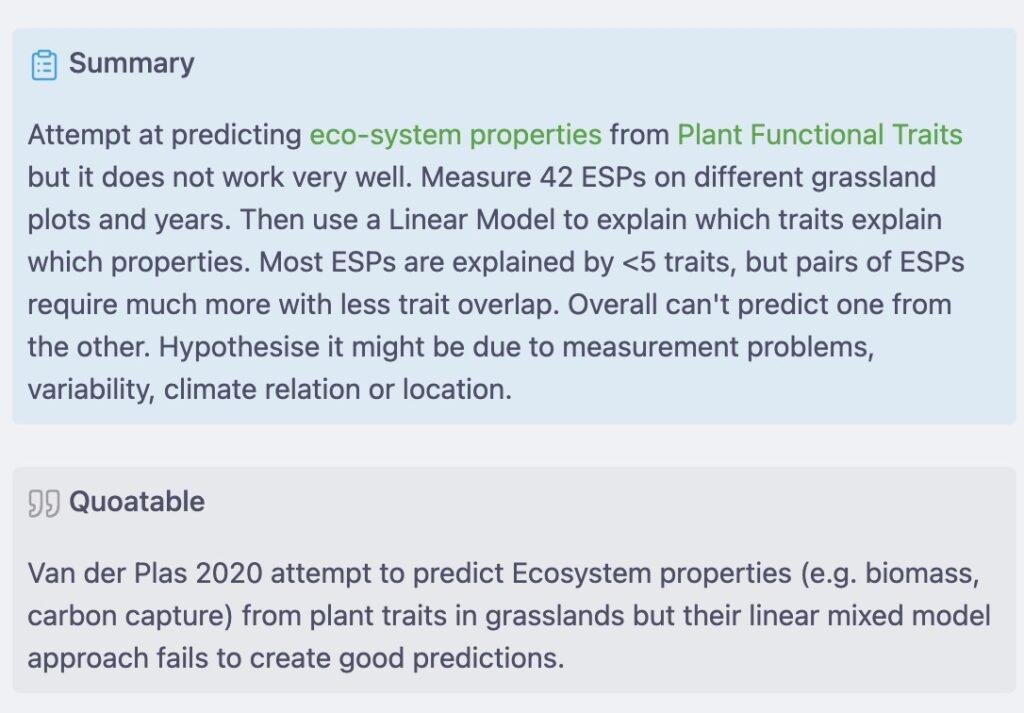

If you think of your notes as summaries you are missing out on a lot of easy productivity. Think of your notes as “building blocks” to assemble a piece of writing out of. When you finish reading a paper, make a quotable sentence out of it, that you can “plug & play” into your writing for example.

These sentences are not summaries. Spot the difference in these two blocks:

See how I can simply throw this “Quotable” block into a piece of writing and have a solid writing prompt. I could even create multiple versions for myself to help future me.

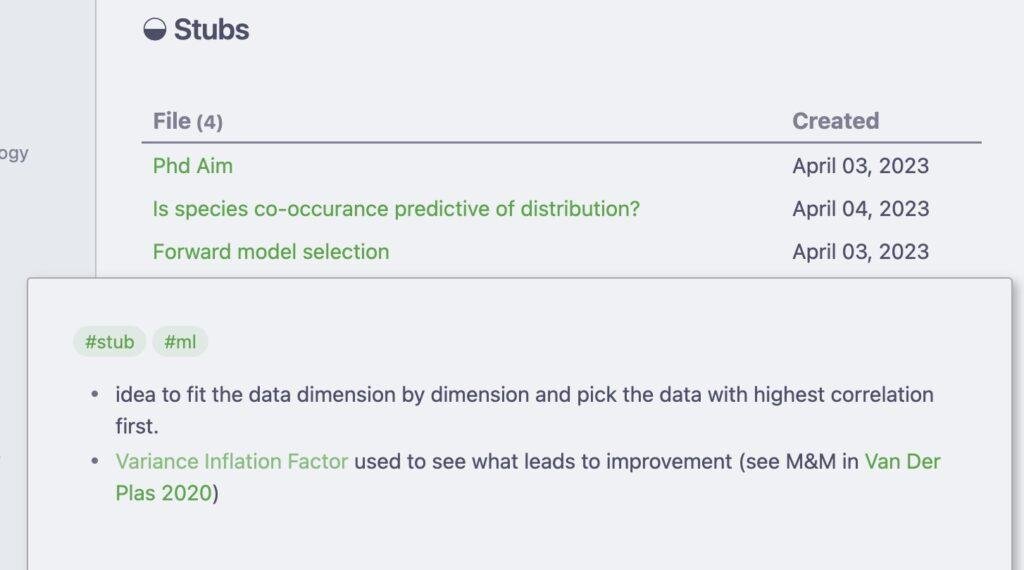

VIII. Thou shalt not ignore gaps of knowledge

Pretty much every paper is filled with things you won’t know. This is normal. You can’t dig into everything but you can’t skip the details either. The problem is we don’t know what is important and what isn’t.

This is where stub notes come in.

For example “Forward model selection” seems important, but I can’t really decide yet if it is worth my time to dig into it right now. So it gets tagged with #stub and ends up in the stubs table:

Notice also that a note-taking tool like Obsidian allows you to create links to non-existent notes. (Variance Inflation Factor is more pale, which means this note doesn’t even exist. Another way of creating stubs.)

IX. Thou shalt automate and learn hotkeys

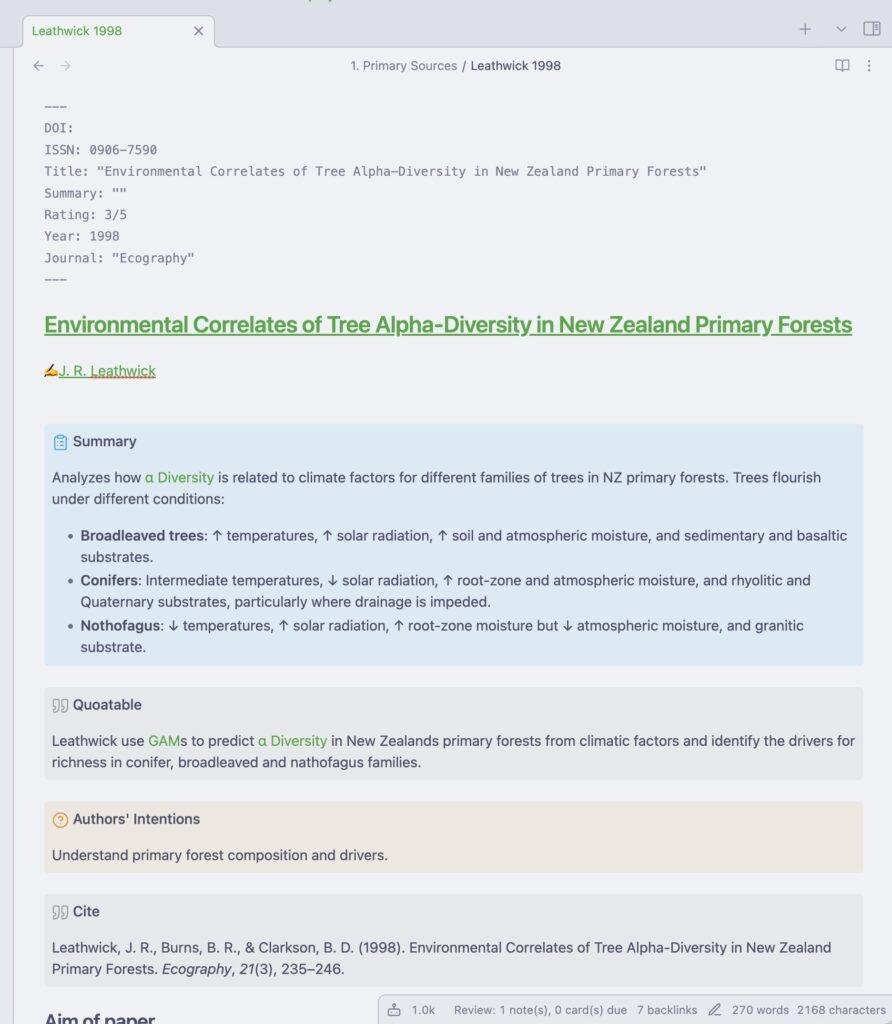

Creating notes quickly becomes a chore. Look at a note I take on one paper.

It contains some machine-readable information at the top, the author, a summary box, well-formatted citations, and more. It would take a long time to do it by hand every time.

That is why modern tools support templates, that I can add with a single keystroke. Even more Obsidian allows you to connect with a reference manager like Paperpile or Zotero and pre-fill some of the data automatically (e.g. the author, title, formatted citation, etc).

Learn these features and hotkeys to eliminate friction from your workflow. More than time it will free up mental space and make work more pleasurable.

X. Thou shalt not lie with another tool

A good craftsman never blames their tool the saying goes. Once you have picked a tool, stay with it. I tried Evernote, Notion and ended up with Obsidian. Your journey might be different, even though I think Obsidian is objectively the most mature tool specifically for academics.

Indeed the more complex a tool, the more likely you will abandon it sooner rather than later. Try to master a tool before looking at the shiny new things that come out. It’s not all gold that shimmers.

Why do I choose Obsidian for my notes?

All the examples here use Obsidian, a note-taking tool. You could also use Logseq or Roam Research or Remnote or Endnote or Notion or many many other tools out there.

Everyone has their own reasons and it is an endless battle for the best tool.

I tried a few but now I won’t trade Obsidian for anything else. Here are my reasons:

Indeed the more complex a tool, the more likely you will abandon it sooner rather than later. Try to master a tool before looking at the shiny new things that come out. It’s not all gold that shimmers.

1. It is offline and blazing fast. Globally search anything in milliseconds.

2. Endlessly configurable. Change appearance, hotkeys even hack how it looks if you want to.

3. Connects well with Zotero, which is great to collect papers and references.

4. Huge plugin ecosystem – with a bit of effort you can achieve anything for free.

5. It’s free and unlimited, even if you store Gigabytes of data.

6. Canvas: A feature where I can lay out my notes and ideas on a 2D mind map and link them.

7. Intuitive and file-based. Obsidian never confused me; it’s mostly obvious how it does things.

8. It is very mature with a huge community and almost no bugs.

The only feature I miss is an easy way to collaborate on notes. That’s why I still like to have Notion as a light-weight sharing tool.

Give it a try!

You can find more in-depth tutorials on Obsidian in my Newsletter or Online Course. Or just follow Twitter for quick tips on how to do research in the 2020s!