How to be an Academic

Every academic journey starts with learning domain knowledge. This however will not make you succeed. What you need is a system to cultivate ideas and channel creativity from many unrelated sources.

Academia is as much an art form as it is an act of engineering.

In my own Master’s thesis I was creating an algorithm that would compare the silhouettes of stone age pottery. After many failed attempts, the solution was built on a speech recognition algorithm. Instead of comparing spoken words, I used it to compare curvatures of millennia-old pottery fragments.

An engineer tries to get from A to B fastest (i.e. solve a problem the best she can). So here we need structure, discipline, and logic – as there is usually a single best way to solve the problem and a clear metric of what is better or worse.

An artist has no problem to solve but channels his own feelings to explore seemingly

unrelated concepts. He creates something unusual, something new and exciting. An

expression of a feeling as color on canvas for example. He needs associative thinking, an open mind, and a relaxed state of mind to channel all of that.

These two sets of skills are a challenging combination. Few people even try, instead, we categorize into “right-brained” or “left-brained” to emphasize that you can either be disciplined and structured OR creative – rarely both.

Yet the academic must do both to succeed.

There is often a clear research goal but there is no method to get there. Creativity AND structure are needed here.

Connections between experiments and established ideas from literature are essential for success. Logic and deduction are as important as intuition and connection.

An Academic is therefore an artist with a goal (or an engineer with a muse).

What Are the Skills Academics Need?

The engineer needs domain knowledge to know what they are doing and a craft to get there. For a software developer, the domain might be “machine learning algorithms” and the craft is coding python and linear algebra.

Think of the domain knowledge as fuel and the craft as driving a car.

The artist on the other hand needs to feed the unconscious to develop curiosity and intuition for deeper concepts as well as a craft (e.g. play an instrument) to express all that.

Popular songs capture the “pulse” of a generation and painters like Gustav Klimt were heavily inspired by scientific developments (Eric Kandel’s The Age of Insight is a great read on how scientists and artists mingled in the late 19th century). The artist always needs to be curiously immersed in what is happening around him.

The academic needs both skills, as they are an artist-engineer. They need to have domain knowledge as well as an intuitive connection with the field they are in. The craft for them may be writing, doing western blots, or coding.

This is why it is such a hard profession. Academics use the rigorous process of engineering, following rules and protocols but must still remain intuitive and “fuzzy” with interpretations and connections.

Think of the discovery of penicillin – Fleming returned from a holiday and found some mold in the petri dish. Instead of following protocol (like an engineer) and tossing it out, he looked at it (curiosity) and realized that the mold prevented bacteria from growing (domain knowledge) and thus started on the path to discover the first anti-biotic (craft).

A Method for Creativity

Honing a craft is conceptually easy, but practically hard: Practice and Repetition. As we all have heard, 10.000 hours of anything will make you a master.

Aggregating domain knowledge is equally easy in theory: Read, study, make notes – live in your domain.

The intuition part is where most are stuck. How do you get a “feel” for the field you are in? How can you practice creative, unorthodox, and original thought?

Turns out there is a tool: Links.

Links? Yes, creativity lives in connection – indeed creativity IS a connection.

If I say “cup” you might think: “coffee”. Then “Sumatra” (where the coffee grows) or

“Starbucks”. We just jumped two links to get from a household item to an island many time zones away.

Poetry or Lyrics in Songs are built on metaphors: “Her hair was like a jungle”. This is multidisciplinary by design. I have to know how a jungle looks and have seen enough people with different hair to understand this metaphor.

To culture creativity therefore we need to make connections: As many and as frivolously as possible.

Now we have established that linking ideas is what we need to be creative and taking notes is what we need for domain knowledge.

Put those two together and you get Linked notes. This is the foundation of an outstanding researcher.

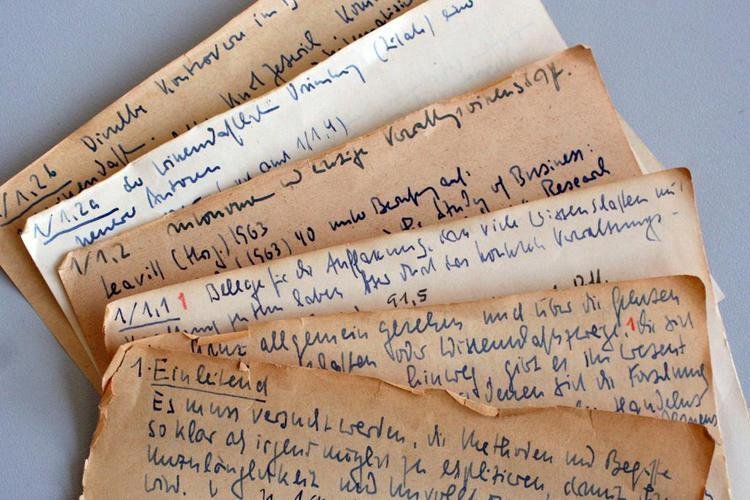

Niklas Luhmann the inventor of the “Zettelkasten” (a type of linked note-taking system) famously published more than 70 books and 400 articles in his lifetime. A good example of unleashed creativity by linked notes.

But don’t bother learning a system as complicated as Zettelkasten right away. You need to let it grow organically, like a garden. This will make it resilient and stand the test of time.

There is a concept called Gall’s Law: “All complex systems that work evolved from simpler systems that worked”. In consequence, it means that designing a complex system from scratch is bound to fail.

Therefore we need to start very simply, before using elaborate templates and systems. And the simplest advice is: “Start linking your notes”.

The Rules of Linking

Having a collection of linked notes will be challenging without a tool that supports it. Luckily the last decade has seen an explosion of those tools: Notion, Obsidian, Logseq, Remnote, Tana to name just very few.

Pick one and take your time exploring it.

Linking notes requires that your notes are taken slightly differently than what you are used to:

❌ Take “sequential” notes. If you read a paper, don’t just summarize it into one big note.

✅ Break your notes into concepts, ideas, and “atomic facts”. These are easily linked and reused.

❌ Take too few notes.

✅ Links to notes with many ideas are not very powerful – since a lot of other notes will link to it. Keep your notes short, quick to grasp, and memorable from reading the title alone.

❌ Take too many loose notes.

✅ Too many notes are hard to find and some get orphaned and forgotten. Every note needs to be firmly integrated into your network of notes from the start to avoid this.

Linked, conceptual and small notes may become chaotic, if you don’t add a few essential elements to manage them. Like a garden that you need to weed and cultivate to keep it productive:

1. Build Maps of Content: These are notes that contain links (and explanations) to other notes. e.g. “Technological advancements of the 20th century” could be a note leading to a plethora of other notes. This will help you navigate.

2. Tag your notes: Try to come up with a system of tags that makes sense to you. Start very broad and re-tag as your notes grow. A shared tag in a note can link it to a dozen of other notes without explicitly having to think about it. Tags become an additional layer of connection.

3. Revisit and relink: Take a walk in the garden of notes that you created. You will notice that certain notes should be linked to some other (newer) notes. Add those links when inspiration comes. Not only will you have better notes, but you will also recall them (as you “touched” them again) and connect them.

Wrap up

The academic is an artist-engineer. They will need the skills of both structure and intuition.

Intuition and creativity live in connecting concepts (like a metaphor). The more connections, the richer your output.

To add creativity to domain knowledge we need linked notes. We make our life easier if we use note-taking software.

Notes need to be “conceptual” or “atomic” – good notes represent a single concept rather than a lecture or a paper.

Heavily link these notes and frequently revisit them to add new connections as your understanding ripens.

To stay organized in the garden of notes, introduce maps of content or (notes that just hold links) and tags. As both will automatically create links between notes.

Start simple, don’t just copy someone’s systems – you need to evolve and earn your structure.

Outlook and Homework

This article is part of a series. Today we looked into the very foundations of why and how to take linked notes.

Next time we are going to dive deeper into a simple system of academic notes. We will add citation management and learn how to annotate a paper to make it work well with linked notes.

Later we will integrate a reference manager like Zotero and elevate our knowledge by using visual thinking.

I have spent years working with note taking systems and after only 6 months my supervisor pointed out “that he could spar with me at the same level as his oldest grad students of 4 years”. This convinced me: Knowledge Management will accelerate your academic journey by orders of magnitude.

You can do the same.

Check out Ilya's:

Your homework until next time is to play around with a note taking app to create a few linked notes.