Rome wasn’t built in one day, a famous saying goes. Things take time – but time alone does

not guarantee that they will get done. If you want to learn something complex, you need a

strategy and a direction.

If you want to write a PhD it gets even more complex as you learn something, that doesn’t

even exist yet. You discover it as you learn

But every challenge has a weak spot and the “weak spot” of science is logic. By this we mean

that complex things build on simple things. Adding 5 to 5, five times gives you 5 multiplied by

5. Multiplication builds on addition. (And indeed a few more logical steps from 5 x 5 and five

years later you are solving “Partial Differential Equation with Space- and Time-Fractional

Derivatives via a Homotopy Decomposition Method”…)

All we need to conquer a complex topic is dividing it into smaller parts and recombining it –

like bricks that build a building. If we additionally connect it to our own ideas, we can produce

novel scientific work.

Here is a simple example. Each puzzle piece is a note that is taken when reading a PDF. Each

concept note on the other hand links back to the paper. This way, if we use this information in

our academic work, we will know who to credit/cite for it.

Unfortunately this is not the way we are used to taking notes. We need a new habit and a new

idea on what note taking is.

How most people take notes

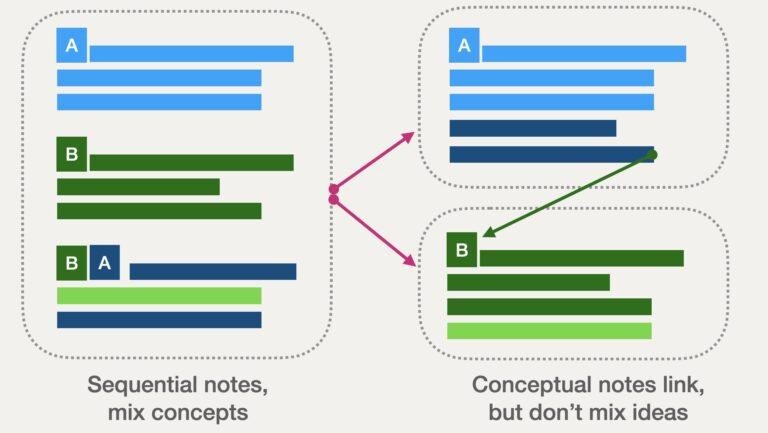

The natural way of taking notes is sequential. The note is simply a running summary of what

you read. As you it helps you retain information, it’s still useful. But you can’t connect

summaries logically into new ideas.

Let’s think of a silly example. Three group of scientist publish three different papers on:

- How to fry the perfect egg

- How to boil potatoes

- How to bake pizza

If you take summaries on these 3 papers you end up with 3 recipes. You will be able to

quickly look up and repeat what they did, which is great as a start – but not innovative!

Let’s say instead you take notes on “Frying”, “Baking” and “Boiling” and then more notes on

“Eggs”, “Potatoes” and “Pizza”. You now have your ideas in a format to come up with

groundbreaking innovations like “Boiling an Egg” or “Frying a pizza”. (Things most PhD

students figure out eventually!)

Separate your notes into concepts. This gives you the freedom to rearrange them, play with

them. Think of how two unrelated ideas might be connected.

Conceptual notes are counterintuitive

Initially when it feels very strange to create 10 notes by just reading one paper. And that’s ok.

Everything in our world is transmitted sequentially. Books, lectures, movies everything

presents information as a sequence: first page to last page.

Naturally we will create notes that look like this.

To train yourself to create conceptual notes try this. Take any long/older note and think of

concepts that you could break out into a separate note.

You will notice that your notes very often have the same structure: “This is idea A, this is idea

B (short paragraphs). This is how A and B are related (another paragraph)”.

Shorten your note by extracting what A and B is into separate notes.

So if you create two new notes instead – one on A, one on B. Everything becomes much

shorter, no repetition occurs.

Repeat this process until your original notes become a collection of links, rather than a note

itself. This is where you reached the conceptual stage.

The perfect note can’t be broken down into smaller notes, but at the same time does not feel

petty or insignificant.

Stub notes

Have you ever started browsing wikipedia at “French revolution” only to find yourself reading

about combat helicopters and Kevin Bacon 15 minutes later?

This happens easily when you read notes. But it also happens when you write them.

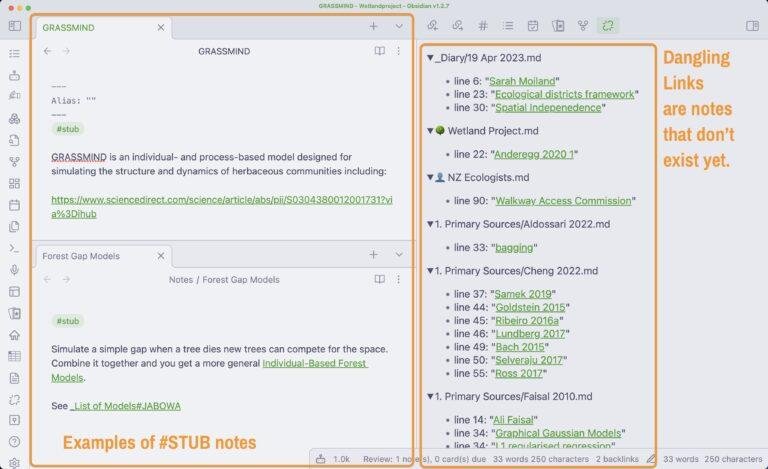

To avoid this a note taking software like Obsidian allows for two methods:

- Create links to notes that don’t exist yet.

- Mark notes with a “stub” hashtag, as a reminder to work on them later

Here are a few examples from my Obsidian vault:

There is a great plugin called “Dangling Links” that will find not-existing links for you.

Create a dashboard for yourself where you store this information, so if you are ever stuck in

your project you work on maintenance of your information. More often than not this will create

new ideas.

Stubs are also a great way to not stray off track when reading a complex topic with unknown

steps.

Let your notes surprise you: Backlinks

Your note collection will be your biggest asset and source of inspiration, once the number of

connections grows. This happens on autopilot, through a concept known as backlinks.

Here is another example. You are studying the proteins A and B in your work and as you read

you connect different diseases, functions and papers connected to them.

At one occasion you find out that A relates to DNA Damage and make a link. At another,

maybe weeks later you find out that B is related to it too.

After forgetting all of that, at some even later point, you open the note on “DNA Damage”.

You ask Obsidian to show you the “backlinks”. These are links that point towards a note.

Normal links are clearly seen in the text but you generally don’t see backlinks without special

software.

In our example you discover that protein A and B both link to “DNA damage”. This

immediately begs the question are they related?

They might be part of a bigger mechanism, they might interact in some way or not at all. But

just having this idea that Proteins A and B are related is creativity.

Best of all you did nothing to have this idea, your notes had it for you. You just linked your

unrelated notes on A and B to “DNA damage” at two different times.

This is the surprise your notes have in store for you, if you take them conceptually and heavily

link them. Check out the article on 10 note taking commandments for more ideas on “good”

notes.

Summary: Divide and Conquer

Sequential notes are not a great way to make notes. Conceptual notes are. While it feels

unnatural to take a dozen notes instead of one big one when reading one paper, it pays back.

It allows us to stumble upon connections we didn’t think of and also to be more concise and

bundle things we know about a certain topic.

Backlinks make these hidden connections visible by showing us the notes that link into a

note, rather than from it. This is only possible with a note taking software – so use one.

Obsidian is my choice.

To avoid digging too deep into concepts when taking notes, it is often enough to just create a

“stub” note. A note that needs some work in the future. It minimizes distractions that arise

from too much detail.

Recently I created a free 7-day starter guide on academic note taking. It will teach you even

more concepts and tools that will make your note taking more innovative and creative.

Join for free under this link: